On Tess Chakkalakal, “Charles Chesnutt’s European Diary” AngloAmericana, special issue of Letterature d’America, vol. 28, Issue 169, 2018, pp. 5-32.

By Morgan Shaffer, PhD Student, University of Tennessee, Knoxville

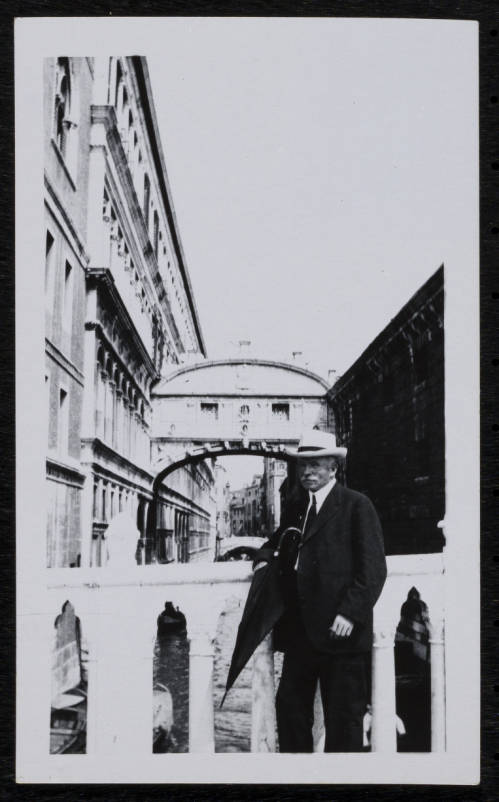

(No photographs of his 1896 trip survive)

Following the tradition of many other American “gentleman writers” who toured Europe as part of their authorial education, Charles W. Chesnutt embarked on a whirlwind tour of his own in August of 1896, keeping a diary of his itinerary and experiences, a departure from the work seen in his Southern Journals, kept between 1874 and 1882. In 2018, Tess Chakkalakal transcribed this diary (housed in the Chesnutt Papers at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland) to make it more accessible to scholars of Chesnutt and of late 19th/early 20th Century American literature more generally. In this diary, Chesnutt’s writing translates the breathless excitement he must have been feeling when seeing great works of art in person, including a viewing of “the famous painting” in the Louvre (most likely the Mona Lisa) and inhabiting the spaces that European literary greats once did (17). His writing in this diary is often sporadic and stilted, clearly scribbled on the page when he found a minute to sit and reflect on all that he was seeing and experiencing, with Chakkalakal noting that “his writing is unusually large and difficult to decipher” due to this (14). She maintains his original line and page breaks, as well as any misspellings, abbreviations, and sentence fragments, which allows the reader to get the best sense of the original material. Chakkalakal’s work to make Chesnutt’s travelogue more accessible, and more easily legible, is to be praised, as reading it is a delight, and one can imagine themselves sat beside him in a rambling train car as he recounts the past few days of art, theatre, sights, and sounds.

Beyond the transcribing work, Chakkalakal’s article uses Chesnutt’s diary to explore the importance this short European trip had on his development as an American writer, especially as one who primarily focused on specifically American issues, most commonly issues of race and oppression in a post-Civil War America. She notes that, though he appears liberated from the race problem in the United States while he is away, not once mentioning the contemporaneously recent Plessy v. Ferguson case, for example, his tour is one of consumption and inspiration, not production. In this vein, Chakkalakal states that “for Chesnutt, Europe was less an alternative to the United States than a place from which he could gain knowledge and experience that could be used to reimagine life in the United States” (11). While Chesnutt appeared to be playing the tourist role for the most part, visiting the Louvre and Anne Hathaway’s cottage, his travels also opened his eyes to a different kind of lived experience for people of color than what he had experienced thus far in the States. Chakkalakal notes that Chesnutt took home more than souvenirs from this trip, he also took inspiration from English and French authors’ presentation of “colored characters” that he felt were lacking in American literature. As a result, he wrote characters like Janet and Doctor Miller in The Marrow of Tradition and John and Rena from The House Behind the Cedars as representations of that reimagination of life in America (10-11). It is this inspiration and reimagination of life through his travels, which he felt allowed him to “’have something worth saying…clearly and temperately’” in his work, per an 1897 letter he wrote to Walter Hines Page, the then-newly-minted editor of The Atlantic (13). Chakkalakal concludes with the sentiment that, while we will never know what would have happened if Chesnutt had followed the advice of his peers and remained in Europe, we, as scholars of American literature, are lucky that he “never gave up on ‘Ameriky’” (13).

While reading Tess Chakkalakal’s article, I had some music quietly playing, as is my habit while reading and researching. I mainly use it as background noise to fill the quiet surrounding my page turning and the dogs snoring next to me. The day I read this article, one song stood out, “Homesick” from Noah Kahan’s latest album Stick Season, wherein he sings about all the things he is annoyed and frustrated by in his Vermont hometown, and yet also that “[he] would leave if only [he] could find a reason,” as well as the refrain of “I’m homesick.” As I listened to the song and read about Chesnutt’s decision to remain an American author in America, I scribbled a note in the margin that reads “missing a place that you couldn’t wait to get away from,” next to my underlining of Chakkalakal’s statement that “for all the pleasure and beauty he finds in Europe, he is still eager to return home to America” (10). As has been discussed above, Chakkalakal notes that many of Chesnutt’s peers would leave the United States, especially in the wake of the Plessy decision, including Albion Tourgée who would move to Europe months after Chesnutt’s return, and yet Chesnutt, who was also very concerned with the fight for African American rights, decided to remain in the States. While we will never be able to read the literature that would have been produced had Chesnutt stayed in Europe for an extended time, or even forever, we can see the inspiration of his time there in his works through the characters like Doctor Miller, who is an educated and talented man who brings that educated talent back to his people. Chakkalakal understands Chesnutt’s desire to return to America as seemingly driven by the need to work from within and uplift other African Americans, both fictionally and in reality. His work created spaces for a variety of representations of African American characters that broke out of the paternalistic molds that contemporaneous authors were utilizing, and which caused Chesnutt to complain to George Washington Cable; he was at least attempting to broaden the understanding of the African American lived experience on paper, especially to white audiences (10-11). Chesnutt likely knew that the fight for civil and political rights was, in the words of Noah Kahan, something that was there before he got here and will be there when he leaves, but he was still going to stay and see it through.